Jim Barnes talks about his tenure as deputy administrator of the EPA when people became aware of the danger to being exposured to radon gas.

A SPEA Professor, An Engineer Named Stanley, Radon, and YOU

In 1984, Stanley Watras was an engineer living in Boyerstown, Pennsylvania and working on the Limerick nuclear power plant near Philadelphia. When he began tripping the radiation monitors going into work, he did more than set off lights and horns. He triggered alarm within the scientific and regulatory community.

“When investigators went to Watras’s home, they discovered it was contaminated by radioactivity from natural, radon-bearing rock formations in an area known as the Reading Prong. The radiation levels in his home were far higher than those in the nuclear power plant, the equivalent of about 200,000 chest X-rays a year. Pennsylvania moved the Watras family out of their home, and with the assistance of the EPA, began testing other homes in the area for radon.

“Radon was not a new problem. Earlier studies had shown that it could cause lung cancer in uranium miners, and there were instances where homes in the Western United States had been contaminated when byproducts from uranium and phosphate mining were used in construction.

“But until Watras’ experience, we had no idea that radon posed a threat to the population at large. Health experts estimated that radon could contribute to, or cause, 5,000 to 20,000 cases of lung cancer a year and that it was particularly a problem for smokers because the particles they inhaled would carry the breakdown products of the radon (radon daughters) deep into the lungs where they would remain and cause harm.

“At EPA, we knew that we needed to quickly pull together a plan for addressing the serious threat to public health – and that it would have to be a nonregulatory program because radon is a naturally occurring substance whose levels vary from region to region and even from home to home, and would require a coordinated effort of state and federal agencies along with the private sector to address the threat.

“Among the challenges we had to address were

- To provide technical assistance to states to identify areas that have the potential for significantly elevated radon levels – and to develop standardized protocols to ensure that radon measurements were comparable and accurate.

- To develop effective and inexpensive techniques to reduce radon levels in existing homes and schools – and to identify and evaluate ways to prevent radon problems from occurring in new buildings.

- To help states and the private sector develop the technical capability to assess radon problems in homes and to help people reduce high radon levels.

- To develop materials that provide information and guidance for citizens: to help them understand how to have measurements made, how to evaluate the health risks associated with high radon levels, and how to reduce those levels."

How to check for radon

- Radon is estimated to cause thousands of lung cancer deaths in the U.S. each year

- Test your home for radon—it’s easy and inexpensive

- Fix your home if your radon level is 4 pinocuries per liter (pCi/L) or higher

- Radon levels less than 4 pCi/L still pose a risk, and in many cases may be reduced

Testing is the only way to know if you and your family are at risk from radon. The EPA and the Surgeon General recommend testing all homes below the third floor for radon.

January is now marked as National Radon Action Month as health officials continue to try to get word out about how to test for radon and enhance their well-being in homes, schools, and workplaces.

James Barnes

“The EPA worked with other federal and state agencies to create what became known as the Radon Action Plan. As the EPA deputy administrator, I chaired periodic decision and coordination meetings, was the lead agency witness in four hearings focused on proposed legislation and implementation of the action plan, and was interviewed several times on the PBS evening news show – ‘The McNeil-Lehrer Report’ – when it focused on the radon issue.

“As I reflect back on my involvement, several events come quickly to mind. The first was a meeting I chaired with EPA and other federal and state public health and environmental officials to discuss and seek consensus on the information we would present to the public about the risks from exposure to radon – and when they should take action to address problems in their homes.

“Two dimensions of the issue presented a challenge for policymakers. One, radon occurs naturally in the environment and an average person is exposed to the equivalent of the risk from multiple chest X-rays a year. We couldn’t assure people that there was a completely ‘safe’ level of exposure. Moreover, we discovered there were limits to how low radon levels could be reduced in homes. So we needed to encourage people to test their homes for radon, to present information that would help them put the risks in perspective, and give them some guidance as to how quickly they should take action as well as an array of options for reducing their risk.

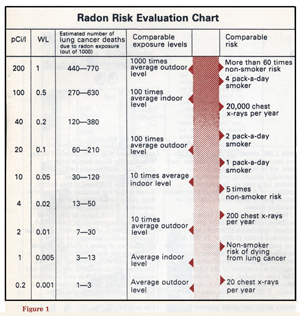

“The meeting produced a consensus on how the risks should be presented to citizens and it was incorporated into a publication A Citizen’s Guide to Radon: What It Is and What to Do About It that has been widely distributed through the years by EPA and state radiation or health protection offices. An important feature is the ‘Radon Risk Evaluation Chart’ (Figure 1), which compares various radon exposure levels to other comparable risks such as from X-rays, smoking, and dying from lung cancer, even for a nonsmoker.

“Both the House and the Senate subsequently developed proposed legislation using EPA’s Radon Action Plan as a base. The Reagan Administration gave me unusual latitude to negotiate with Sen. George Mitchell (D.-Maine). We quickly reached agreement on a version that the Administration would publicly support. It was the only occasion in my time in government where I could point to a personal role in the specific language in legislation that ultimately became law.

“I testified before a House committee considering that legislation and was followed to the microphone by Sen. Mitchell who concluded his testimony with this:

“‘I just want to make a note that the reason we got a bill passed in the Senate was because of the cooperative attitude of the EPA and specifically Mr. Barnes. We negotiated with them. We did not agree at the outset. We worked out a compromise. I commend him for the good faith and diligence he demonstrated in reaching that compromise.’ “The aura of good feelings, however, ended quickly. Two House Democrats wanted EPA to establish a standard for radon exposure that was below the natural background level in the outdoor air. We strongly disagreed. We were concerned that people would get confused and miss the primary point: You can detect radon in your home and, when it is present, take readily available steps to reduce the risk. Our position prevailed, the legislation based on our approach was adopted, and it has stood the test of time.

“The elements in the program today and the message concerning the problem and what people could do about it are those we put in place some 30 years ago. Monroe County, home to Indiana University, is one of many in Indiana with predicted average indoor radon screening levels that necessitate action. “It is a threat that will never go away. I’m proud of the response by federal, state, and local officials – and by the private sector. And, we can all be grateful that Stanley Watras set off the alarm that resulted in a program that has saved lives.”

SPEA looks for water solutions

While radon was an emerging health threat in the 1970s, the safety and supply of our drinking water is under the microscope now. Many SPEA faculty members study water science and policy. For example, Todd Royer leads a team of researchers that has developed a project among the five finalists in IU’s Grand Challenges Program. The $300- million program will fund three to five initiatives over the next five years that will each take on major and large-scale problems facing society. It is the single largest research investment in IU history.

Royer’s team plans to develop and demonstrate new technologies, data systems, and policy arrangements for sustainable management of water resources in support of human welfare and environmental quality.

Water scarcity, poor water quality, inadequate infrastructure, and governance failures are persistent and growing threats to the world’s water supply.

Royer says Indiana University is uniquely positioned to address this challenge. His team’s proposal leverages IU’s renowned strengths in natural sciences, governance, and computing – a powerful combination that, when brought to bear on water resources, can offer robust and innovative solutions.

Their goals include:

- establishing integrated networks of information regarding water supplies, quality, uses, and infrastructure;

- creating tools for water resource planning, decision-making, and adaptive governance that consider political economy, cultural constraints, and the differential value of water across sectors of society; and

- developing and applying new tools and products to address and reverse threats to water quality and repair imbalances in the water-food-energy nexus.

Throughout the project, research will first be focused locally, ensuring early benefits for the state of Indiana, with potential for adaptation to national and global applications.

SPEA faculty members are also involved in several of the other Grand Challenge finalists. Joe Shaw’s team hopes to create a healthier environment for the people of Indiana and beyond. They plan to translate 21st century research about chemicals, their movement, and impact on the environment and human health into profound breakthroughs in knowledge for effective governance, responsible innovation, and economic growth.