Predicting the future is a dicey game.

By Elisabeth Andrews and Jim Hanchett

By Elisabeth Andrews and Jim Hanchett

In 1909, Nikola Tesla told The New York Times: “It will soon be possible to transmit wireless messages all over the world so simply that any individual can own and operate his own apparatus.”

Tesla was right.

Then there was the prediction from Guglielmo Marconi: “The coming of the wireless era will make war impossible, because it will make war ridiculous.”

That may be true one day, but not yet.

As SPEA prepares for 2020 and beyond, we sent wireless messages to several SPEA faculty members and asked them to look into the future. Gamely, they offered these takes on likely developments in their fields that will affect us all.

Vacuum-powered mass transit, electric cars, and alternatives to the fuel tax are all likely to advance by 2020, says SPEA Assistant Professor Denvil Duncan. Five years from now, he predicts, we could start to see daily commutes, intercity travel, and government budgets all moving away from dependence on fossil fuels.

SPEA asks, Denvil Duncan answers.

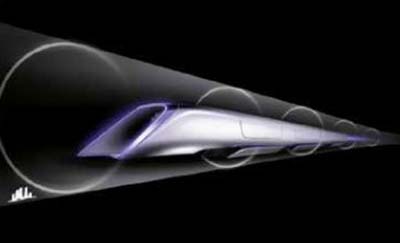

Duncan: The biggest out-of-the-box idea that’s being explored is the Hyperloop, which would allow a passenger pod to travel through a pneumatic tube at extraordinary speeds. You may have seen smaller-scale capsule systems like this – for example, in drive-up banks. The idea for the passenger system started with [Tesla Motors CEO] Elon Musk, but now several companies are exploring its feasibility.

Duncan: From the specs I’ve seen, you’d have an above ground tube, probably over existing highways. The partial vacuum makes it possible to go several hundred miles per hour. Cabins would need to be pressurized, like on an airplane. It’s all electric powered, so you have the advantage of reducing fossil fuel dependence. It could compete with air travel, at least for shorter distances – it’s expected to be more efficient for trips up to 900 miles. I don’t think it would take you east to west across the country, but eventually we could have networks linking many cities.

Duncan: Within five years we will actually have tests taking place to determine the safety and reliability of the technology. Construction on a prototype is expected to begin next year in California, so we should know by 2020 whether it works or not.

Duncan: I think it will really depend on Tesla’s Model 3 [all electric car], which will be available in the next few years. The plan is to produce a car in the $30,000 - $35,000 price range. If they succeed in producing it at that price point, I think it will make a big difference in electric’s ability to compete in the market. My own view, without having done a lot of research in this specific area, is that the viability of electric as an alternative to fossil fuel will come down to Tesla. They are one of the few companies that are fully committed to electric, so they have an interest in seeing the technology go forward. I don’t think we can rely on manufacturers of gasoline-powered vehicles to move us toward an electric fleet.

Duncan: I’m a sci-fi person, just to be clear. I would bet on the Hyperloop or something similar before I’d imagine people walking or riding bikes.

Duncan: Culture is not easily changed. There is a preference, especially in the Midwest and the South, for these large vehicles. But what we do see is greater interest in fuel efficiency. Some of the newer trucks and SUVs are getting upwards of 22 and 30 miles per gallon, respectively. However, the focus on fuel efficiency is creating new problems for policymakers, because transportation budgets are funded by gasoline taxes.

Duncan: Right now, the tax is assessed per gallon – 18.4 cents to the federal government and in some states a higher amount. The current projections show us losing fuel tax revenues but people driving the same amount, so we’ll still have the wear on the transportation infrastructure but fewer funds to repair it.

Duncan: The strategy that I like is to switch from a fuel tax to a mileage user fee. If you do that, the revenues increase with the demand. It’s not a very popular idea, though, because you’d have to track mileage with some kind of GPS reporting system, and that’s seen as an invasion of privacy. On the other hand, your movements can already be tracked with your cell phone records, so while I don’t want to diminish those concerns, it’s not the worst type of surveillance. One way around that issue is to let drivers choose a private company to hold their information. Oregon is set to start testing a system like this on a voluntary basis this year. It will be very interesting to see how it changes driving habits. The gas tax is well hidden – I ran a survey recently and less than 15 percent of people could identify the price range of their gas tax – but the mileage user fee would be staring you in the face. It’s also a hard sell for people with fuel-efficient vehicles, because Oregon’s system is set up to be revenue neutral for an average fuel efficiency of 20 miles per gallon. If you get better mileage than that, you’ll pay more than you would with the gas tax. By 2020, we should have some results from that experiment.

The digital revolution moved the bulk of entertainment to individual's devices, but Professor Michael Rushton, director of the SPEA Arts Administration Program, predicts this trend will shift by 2020. Not only will people be attending more live events, he says—they'll also be making more art for their own enjoyment.

SPEA asks, Michael Rushton answers.

Rushton: There’s no question that people will continue to have options for entertaining themselves on their phones and computers and TVs – even video games, which I personally think have had a big impact on the arts by competing with the music business. But at the same time we’re seeing more communities creating entertainment and arts districts. As we approach 2020 I think we’ll see local governments really emphasize this creative place-making and partnering with arts and culture organizations.

Rushton: Yes, in fact [SPEA Assistant Professor] Joanna Woronkowicz and [SPEA Associate Professor] Doug Noonan and I have all been researching the impact of the arts on economic growth, and it’s clear that cities are using the arts to attract residents and businesses. People want to live in interesting places. One of the bigger trends is that younger people increasingly want to live in city centers rather than suburbs. They’re not doing that just so they can sit in their apartments. They want things to do.

Rushton: The good news for arts organizations is people are becoming less interested in accumulating “stuff” and more focused on having memorable experiences. But pricing is a real challenge, because you have some people on the fence who aren’t sure they are going to like something or don’t have a lot of money to spend, and then you have others who are happy to pay, and you want to get as much financial support as you can from them. My most recent book is called Strategic Pricing for the Arts, and it goes through a lot of different ways to approach this problem through things like discounts and memberships and special exhibits.

Rushton: It’s really hard to do. With most types of businesses you can get a sense of demand, but every performance and piece of art is unique. You don’t know what’s going to succeed until it’s out there. We talk a lot in our arts administration classes about dealing with this radical uncertainty. You have to be ready for any type of critical and commercial response.

Rushton: We’re getting more people traveling to festivals of all different kinds. People like the collective aspect of that – being with all these other people enjoying the same thing. But a crucial point is that people don’t just want to be audiences. They also want to create things. We’re seeing a comeback in people engaging in arts and creative activity. It’s not just about going to see what someone else has made.

Rushton: Yes, I do. Retired people want to do things: draw and paint, make music, dance, cook. I see this as a growing sector.

Rushton: I think we’re going to see more public art and more street beautification projects that incorporate artistic elements. There’s going to be an increasing intersection of arts administration and urban planning. SPEA can have an exciting role in supporting that growth because of our research strengths in both areas.

Efforts to equalize public school funding have had the unintended consequence of reducing overall revenue, while wealthier areas have continued to find workarounds, says SPEA Associate Professor Ashlyn Nelson. Improving school funding will require greater transparency at the district level as well as tax policy updates “to create a bigger pie.”

SPEA asks, Ashlyn Nelson answers.

Nelson: Right now, on average, 40 to 50 percent of public school funding comes from the state and another 40 to 50 percent is coming from local sources – mostly property taxes. Only about 10 percent comes from federal sources, and those are typically considered “compensatory” funds for educationally disadvantaged students in high-poverty areas and special education.

Nelson: It’s considered the state’s domain. Each state’s constitution specifies the extent to which it is obligated to provide a public education. In many states the language refers to an “adequate” education, so you wind up with a lot of discussion around what defines adequacy.

Nelson: This issue was the focus of school finance lawsuits in the 1970s and ’80s that resulted in property taxes being redistributed to districts via school funding formulas. These funding formulas often reallocate property tax dollars to districts on the basis of student need. Those funds supplement additional federal funds aimed at low-income students and those with special needs. As a result of both these redistributive policies and federal funding, many poor districts receive more funding on a per-pupil basis than do their wealthier counterparts.

Nelson: Two reasons. First off, wealthier districts responded to the funding equalization measures with property tax revolts. In many states, we wound up with very restrictive property tax limitations, so that even though the money is distributed more equally, there’s less of it. Second, in most states, once the money gets to the districts, they are not required to report on how it’s spent. Most likely the bulk of it goes to the schools that are already performing well, because that’s where you find the higher salaried teachers.

Nelson: I’m really surprised that more haven’t tried. But recent attempts in Pennsylvania collapsed when the districts argued they didn’t have the resources or training to track spending. We’re going to have to overcome those practical constraints because we’re left without a means to measure productive uses of funding. Instead, we wind up with studies that say more money doesn’t equal better outcomes, but it’s ridiculous to say money doesn’t matter when you don’t know how the money is being spent.

Nelson: A lot of my research has focused on this question of alternative revenue-raising mechanisms. Two recent trends are local referendums and voluntary contributions, some of which are coming through school-supporting nonprofits, which I wrote about with [SPEA Associate Professor] Beth Gazley. But both of these trends are predominantly occurring in areas with high property values and median incomes. So, essentially, these workarounds are on their way to upending 40 years of school finance equalization efforts.

Nelson: We’re going to have to create a bigger pie to fund education. We face a lot of pressure to spend more on public education, not only because the number of students enrolled in public schools is projected to increase by more than 3 million in the next decade, but also because U.S. students demonstrate comparatively weaker skills in mathematics than do our Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development peers. We need to increase the rigor of our coursework in order for U.S. students to compete successfully in a global knowledge economy.

I have a few suggestions for increasing the flow of tax revenues to public education. At the local level, we could increase the property tax base by ending property tax exemptions among nonprofit organizations and/or making homestead exemptions less generous. At both the local and state levels, funding for education faces competition from funding for other public services. Thus, any policies that improve state and local revenues may free up additional funding for public schools.

E-commerce has a substantial adverse effect on state and local sales tax revenues. Consumers often purchase goods and services online using out-of-state vendors in order to avoid paying sales and use taxes at the state and local levels. Congress is currently considering the Marketplace Fairness Act, which would require online vendors with annual revenues exceeding $500,000 to collect and remit state and local taxes for out-of-state sales. The Marketplace Fairness Act is one example of tax reform that may benefit public schools by improving the flow of revenues to state and local governments. At this point, the House of Representatives has not yet enacted the act, though the Senate passed the act in 2013.

At the federal level, substantially higher tax revenues could be collected if the federal government ended the mortgage interest deduction. However, it is unclear whether Congress will be able to pass such a landmark tax reform. The mortgage interest deduction is very popular among homeowners, though it is widely viewed as inequitable because it disproportionately benefits high-income taxpayers who itemize their deductions.